|

Cold War Warriors Cold War Fallout - Part 2

Captain Edmond D. Pope, USN Ret

(11/2012) This is the second in a series of articles describing the 1990s collapse of the Soviet Union and its transition toward a modern Russian state. (Read part 1) The observations are based on my own experiences and I hope they provide the reader with some

appreciation for what the average Russian was going through during this chaotic and historic period. It was a confusing and complicated time that is difficult to describe unless you were there. I spent most of my professional career studying the Soviets. What I saw and experienced during my travels throughout the 1990s surprised, amused, saddened, and sometimes shocked me.

Through it all, I was fascinated and impressed by the resilience, intelligence, ingenuity, and perseverance of the Russian people.

Post-Soviet Logic

In September of 1993 I spotted a souvenir that I had been looking for at Moscow’s enormous, Ismailovo outdoor market. I had come to enjoy my frequent, free-time, visits to this large flea market. The market seemed to grow larger each time I traveled to Russia. A vendor asked six rubles for the item I was interested in, so I asked if he would take 10

rubles for two of them. It was considered an insult if you did not bargain. "Of course" he replied while beaming at the possibility of a sale. I had a number of friends back home who would cherish this particular item so I asked him what price he would give me if I took ten of them? He thought for a moment and replied "eighty rubles!" with an even broader grin on his face.

|

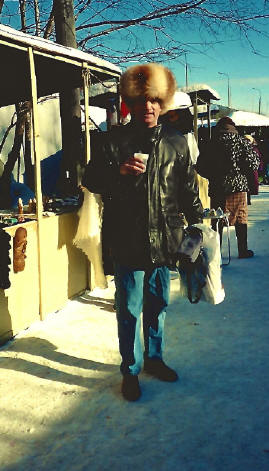

Author Edmond Pope dons his brand new Russian hat (i.e. furazhka) he just purchased at an Izmailovo market kiosk.

|

Now, I was no Einstein but his logic just didn’t make sense to me. So I made the mistake of playing a simple game with him. After I bought the first two items that he had offered for 10 rubles, I immediately asked him for two more at the same price. He refused, saying he wanted twelve rubles for the second two and that, if I wanted ten of them, the

price would have to be eighty rubles. After having this verbal exchange several times and doing the math on a piece of paper for him to examine, I gave in and asked him to please explain his logic. He said it was all very simple - "if you like them enough to buy more than one then they must be valuable to you so I must get a higher price for all others you buy." Karl Marx

would have loved this guy.

This strange view of "business" to the Russians of the early-1990s was not limited to the street vendors. On several occasions, I encountered senior managers and executives of Russian enterprises who openly admitted that they had no idea what the price should be for their products or services- that they would appreciate my help at setting a figure.

Left to their own devices, I was often quoted a price that was ridiculous. A joke! Were they serious?

One particular case comes to mind. An office at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington D.C. had asked me to negotiate a contract for them. They wanted to do some work with a formerly secret facility near Gatchina, just south of St. Petersburg. The Russians wanted to do the work, but had no idea how to turn their ideas into a legal contract.

I spent most of a morning negotiating the particulars of a contract. Getting general agreement on the time and materials that would be required to do the work. Finally, I created a draft "statement of work" which described exactly what would be required. Then it took them about two hours to translate it into Russian. After that, the Russian researchers

and their supervisors reviewed the document in painful detail and emerged proudly with a document that they all had accepted. When I asked what their price was for this work- they said that they had no idea. They did not know how to price their work. I then explained how we might convert the work statement into a cost proposal that could be put into the contract. I gave them

a draft of a standard cost-plus "fee" (i.e. their profit) contract.

The proposed contract described their total labor, cost of materials, shop expenses, administrative overhead, and provided for a reasonable profit. They liked this and became very excited. They took the draft contract into their private meeting room and soon presented me with a finalized contract. Knowing what such work would cost back home, I was

expecting a total contract cost of around $50,000 - certainly not more than $75,000. That would give us room to negotiate. I was dumb struck when the price tag they presented to me was $1.5 million. Again, maybe Karl Marx would have understood - I was speechless.

Another observation from that trip to Gatchina involved a "very special" tour the Russians had arranged for me through one of their secret "museums".

The tour was at the formerly, classified research institute known as Prometey; the "Central Research Institute of Structural Materials". A center for development of sophisticated, modern materials during the Cold War. My visit was hosted by the Director of Prometey, Academician (Professor) Igor Gorynin, a full member of the both the Soviet and Russian

Academy of Sciences and a worldwide leader in the development of weldable, titanium alloys for submarines and spacecraft. In 1989, just before the collapse of the USSR, he was elected to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union.

Gorinin had arranged to give me a personalized tour of the Prometey museum that day and it was an honor that I will never forget. However, I did manage to find a humorous side to the tour as well. I was shown diagrams of sensitive submarine construction "details" (i.e. assemblies, components or parts) and specialty materials that Prometey had developed

over the years. One of the museum’s displays was of a large bellows formed from titanium. I knew enough about titanium to appreciate the difficult manufacturing process they must have designed to shape that part. They also displayed a shovel blade made entirely from titanium. Impressive. A couple of years later I would find and buy 4,000 titanium shovels from Russia’s major

titanium plant in the Ural Mountains.

Cigarette,ashtray in St. Petersburg International airport. To some a Cold War,

classified, titanium "assembly" for the Soviet military.

To others … a "butt can" for the modern, Russian, Marlboro Man.

However, on the day I toured Prometey’s museum, both the titanium bellows and the shovel were deemed "too sensitive" for me to photograph. Several months later- while waiting for a flight out of St Petersburg- I spotted an identical, titanium bellows. This one was clearly not under any secrecy restrictions. In fact, it was being used as an ashtray for

smokers at the airport.

WHAT A COUNTRY!!!

To See a Man Cry

In Soviet times, there was plenty of money (rubles) to go around but it was difficult to find anything to buy that was needed or desired. Typically, the best and most sought after goods were found and bartered for on the street through the "black" economy, mostly foreign goods that had somehow been smuggled into the country. Most food and consumer

goods were sold through official State stores, including the "world’s largest shopping mall - G.U.M. (Main Universal Store)- the giant, department store on Red Square across from the Kremlin and Lenin’s tomb.

To a Westerner, the imposing exterior of GUM would lend itself to visions of modern, western shopping malls. However, once inside, one would immediately see the same small drab specialty kiosks that were typical everywhere in Russia. Dirty, drab, colorless, half- or completely empty shelves and burly, sour sales people. Even these Soviet-style kiosks

attracted a crowd whenever they received any kind of supply of product to sell. Word would quickly spread and in short order a crowd would be lined up to be able to "buy" whatever it was they had. If it wasn’t the size, color or shape you desired, that was not a problem. You could take what you did succeed in buying and resell or trade it for something you did want on a

street "black market" line. In order to acquire any product in one of the state stores, you had to endure a torturous time-consuming ritual of insults that most citizens detested.

A Moscow street market. A refreshing change from the state run stores. Here you could

see what you were buying and could barter for a decent price.

Upon entering one of these kiosks, you would wait in a line and, if so lucky, be given a voucher indicating that you had succeeded in being early enough to obtain a loaf of bread, a pair of shoes, a hat, or whatever it was that was for sale that day. Then you would proceed to a second line and once again wait until a burly cashier graced you with her

acknowledgment that you existed. You would then hand her the voucher you had been given in the first line and pay the price for the goods you were authorized to purchase. She would then give you a paper receipt indicating you had paid for the item and you would move along to a third line. Here, you patiently waited until you got to the head of the line and the matron decided

to wait on you. Upon handing her your voucher and receipt, she would give you the new pair of shoes that you had just purchased. All in all … a successful day at the GUM and it only took you an hour or two … or three? The time saved is another reason citizens liked to buy from street vendors. Here they could sometimes find what they really wanted and not have to suffer

through a bureaucratic process.

The process for purchasing an automobile in Soviet days was very similar to that described for a pair of shoes at GUM - except that it normally would take several years to take delivery. One time, a good Russian friend of mine who lived in Moscow picked me up at Sheremetyevo Airport in his brand new Lada automobile. Remember the old saying about the

Lada when the Soviets tried to market them in the West? "Lada- rhymes with Nada! " Anyway, my friend was extremely proud of his new Lada. This was the new incarnation of Lada designed by Fiat and, my friend proudly explained, it only took him four years to get his car. His Lada was like new. It had about 400 km on it (i.e. 250 miles) and I noticed that before we departed the

airport we had to pull over because it was raining. He asked me to help him retrieve the windshield wipers from the glove compartment. We attached the wiper blades to the motor mechanism. Finally, he handed me a branch from a bush that was about three feet long. He explained that I would need to help anytime the wipers were needed. Only the driver’s side motor connection

worked and every time it wiped one time across the window- the two wipers would become stuck together- rendering them useless. It was my job to roll my window down and poke the two wiper blades apart so they would make one more swipe across the window. I asked him why he didn’t just use the driver’s side wiper and leave the passenger blade in the glove compartment? His answer

made perfect sense- "Is not allowed to only have one. Police would pull us over and give me ticket."

Following this, I asked him a few other questions about his car such as "Why doesn’t your gas gauge work?" His answer: "Oh, none of my gauges work. This is new car and most new cars need many repairs in order to get all parts to work." Once again I showed my ignorance of their system by stating that I understood that he probably just had not had a

chance to take the car in for warranty work. He was fluent in English and understood Western ways. So he just laughed and explained that, in Soviet times, when you bought a new car you owned it completely …. even if you had to push it off the sales lot. Also, any and all repairs needed were to be taken care of by the buyer. Clearly he had a good sense of humor. Whether it was

a new car or a loaf of bread, this was the way everything "worked" in Soviet times. Oh, and the reason he kept his wiper blades in the glove compartment? They would be quickly stolen if they were left overnight on the car. Little wonder that the people of Russia and other former Soviet states were so excited about a new and better life that awaited them- after Communism.

Not all of my experiences with the changing Russia transpired inside that country. I had close interface with many Russians here in the U.S. in the 1970s and 80s. They were mostly the Soviet, scientific elite who traveled here seeking work and collaboration. Also, there was a flood of émigrés

and even defectors who somehow got out of the USSR in the waning years of the Cold War. They came with high hopes for a better life for themselves and their families. Many were the times that I witnessed their disbelief eventually turn to awe, envy … then disbelief and wonder at the abundance and quality of food and consumer goods available in the West and the U.S. I would

better understand their feelings after I began my travels to their country in the early ‘90s.

One incident in particular almost brought tears to my eyes- and did, in fact, bring a Russian scientist, in his mid-60’s, to tears and total confusion. This individual was a well-known scientist in his particular field and we (the U.S. Navy’s Office of Naval Research) had arranged a visiting professorship for him at a top U.S. university. He flew

directly in from Russia and I met him at the airport and took him to the university campus. We provided a day for him to rest before meeting his future colleagues. He asked if there was somewhere that he might buy a pair of shoes and a few toiletries. I took him to a local, Wal-Mart – not thinking of the store’s impact on a newly arrived, Russian visitor. We entered the store

and he immediately became visibly nervous as I escorted him through the various departments. The shelves were piled high with goods….some that he recognized and others that he probably did not. Finally, we came to the shoe department and I walked him to the men’s section and told him to select the style he liked. At this point, I could see he was not only totally confused,

but also somewhat frightened. I explained that all he had to do was select the style and size he wanted and take them to the front of the store and pay for them. He broke down and began to cry, something that I would experience many times while hosting Russians to the U.S. for their first visit. I later visited several stores that we take for granted and all my guest could

say was "My wife will not believe this. I can’t wait to show her."

Are We Creatures of the same Planet?

My many trips to Russia witnessed rapid change in their society and the above vignettes only begin to express the many unusual things that I observed. The collapse of the Soviet Union and establishment of an independent Russia and other republics- left the people with long pent-up hope for things they had only dreamed of in silence for years and

decades. Should they speak out openly in the past, they might well end up in prison or worse- in a forced labor camp (gulag) in Siberia, unlikely to ever return to family and friends. Almost every friend I met and got to know, had family members who had been so banished. It was a sad thing to listen to, but left an indelible imprint on my own thinking.

Unfortunately, I will have to skip over many observations from this time and "fast forward" several years. To a time when the hopes and dreams of the early 1990s came to grips with the harsh realities of life in the late 1990s. Many Russians that I knew, foresaw these harsh realities and did not relish what they saw. But, that is another story- Part 3

of the "Cold War Fallout".

Edmond D. Pope is a retired Navy Captain and former Naval Intelligence Officer. Following retirement from the Navy he was employed by Penn State’s Applied Research Laboratory. He was accused

and convicted of espionage by the Russian government in 1999. More about his adventures in Russia can be found in his book "Torpedoed" and at his Web site http://edmondpope.com/ . Edmond Pope currently lives in State

College, PA.

Read other articles by Captain Edmond D. Pope

Read other Cold War Warrior

Articles

|