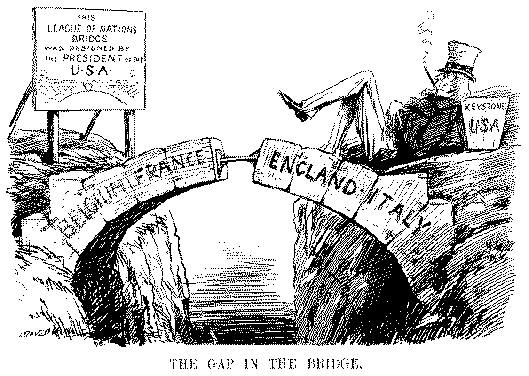

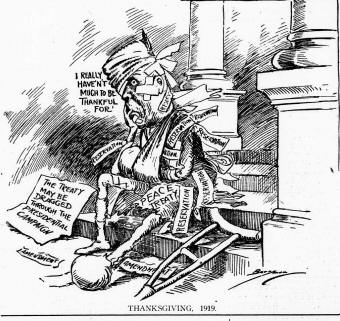

In November 1919, for the first time, the Senate rejected a peace treaty. By a vote of 39 to 55, far short of the required two-thirds majority, the Senate denied consent to the Treaty of Versailles. President Woodrow Wilson personally negotiated the treaty ending World War I, promoting within the treaty the charter for the League of Nations, which

he hoped would provide for a system of collective security.

The League of Nations was the first worldwide intergovernmental organization whose principle mission was to maintain world peace. The Leagues’ primary goal included preventing wars through collective security, disarmament, and settling international disputes through negotiation and arbitration.

The League of Nations posed ideological problems for many Republicans, including Henry Cabot Lodge. Most contentious of its propositions was the Covenant that called for the League to arbitrate the legality of actions within member countries and the placing of the U. S. military under the command of foreign leadership to be used, without the

consent of congress, to maintain peace in areas where the U.S. had no national interest.

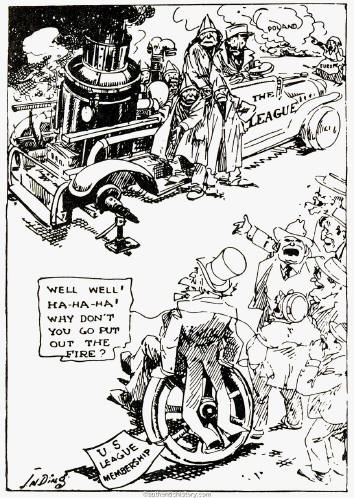

After some notable successes and some early failures in the 1920s, the League ultimately proved incapable of preventing aggression by the Axis powers in the 1930s. The credibility of the organization was weakened by the fact that the United States never joined the League. The onset of the Second World War showed that the League had failed its

primary purpose, which was to prevent any future world war.

In the course of the diplomatic efforts surrounding World War I, Britain, the leader of the Allies, and in the neutral United States, long-range thinkers had begun to design a unified international organization to prevent future wars. President Wilson, in his Fourteen Points peace plan of January 1918, included a "League of Nations to ensure peace

and justice."

President Woodrow Wilson oversaw the drafting of a U.S. plan, which reflected Wilson's own idealistic views. Wilson's own first draft proposed the termination of "unethical" state behavior, including forms of espionage and dishonesty. Methods of compulsion against recalcitrant states would include severe measures, such as "blockading and closing

the frontiers of that power to commerce or intercourse with any part of the world and to use any force that may be necessary..."

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Wilson put forward his draft proposals. After lengthy negotiations between the delegates, the draft was finally produced as a basis for the Covenant for the League of Nations. After more negotiation and compromise, the delegates finally approved of the proposal to create the League of Nations and the League

was formally established by Part I of the Treaty of Versailles.

Structure of the League

The League was made up of a General Assembly (representing all member states), an Executive Council (with membership limited to major powers), and a permanent Secretariat. Member states were expected to: "respect and preserve as against external aggression" the territorial integrity of other members, and to disarm "to the lowest point consistent

with domestic safety."

All states were required to submit complaints for arbitration or judicial inquiry before going to war. The Executive Council would create a Permanent Court of International Justice to make judgments on the disputes.

The League held its first Council meeting in Paris in January 1920, six days after the Versailles Treaty and the Covenant of the League of Nations came into force. In November 1920, the headquarters of the League was moved from London to Geneva, where the first General Assembly was held.

The main constitutional organs of the League were the Assembly, the Council, and the Permanent Secretariat.

Unanimity was required for the decisions of both the Assembly and the Council. This requirement was a reflection of the League's belief in the sovereignty of its component nations; the League sought a solution by consent, not by dictation. In case of a dispute, the consent of the parties to the dispute was not required for unanimity.

The Assembly consisted of representatives of all members of the League, with each state allowed up to three representatives and one vote. The League Council acted as a type of executive body directing the Assembly's business. It began with four permanent members (Great Britain, France, Italy, and Japan) and four non-permanent members that were

elected by the Assembly for a three-year term. The first non-permanent members were Belgium, Brazil, Greece, and Spain.

The League also oversaw the Permanent Court of International Justice and several other agencies and commissions created to deal with pressing international problems. These included the Disarmament Commission, the International Labor Organization, the Mandates Commission, the International Commission on Intellectual Cooperation (precursor to

UNESCO), and the Court of International Justice.

The Permanent Court of International Justice heard and decided international disputes which the parties concerned submitted to it. It also gave an advisory opinion on any dispute or question referred to it by the Council or the Assembly.

Rejection of the League by the U.S. Senate

Woodrow Wilson saw the Allied victory in World War I as an opportunity to revise the international order. At the peace negotiations in 1919, Wilson successfully argued for the creation of a League of Nations. Many Americans, however, believed that

membership in the organization might require American entry into a future war.

Woodrow Wilson saw the Allied victory in World War I as an opportunity to revise the international order. At the peace negotiations in 1919, Wilson successfully argued for the creation of a League of Nations. Many Americans, however, believed that

membership in the organization might require American entry into a future war.

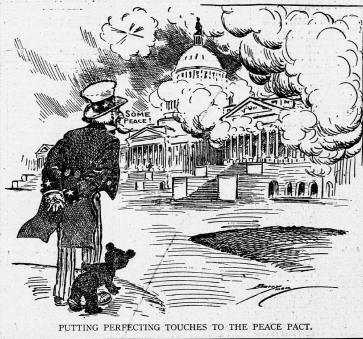

Despite Wilson's efforts to establish and promote the League, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919, Senate Republicans led by Henry Cabot Lodge wanted a League with the reservation that only Congress could take the U.S. into war.

When the treaty arrived in the Senate in July, Democrats mostly supported the treaty, but Republicans were divided. The "Reservationists," led by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, called for approval of the treaty only if certain reservations, or alterations, were adopted.

In August, Lodge reiterated to the Senate that Article X of the League violated the principles of the Constitution. He stated that no American soldier or sailor could be sent overseas to fight a war "except by the constitutional authorities of the

United States."

In August, Lodge reiterated to the Senate that Article X of the League violated the principles of the Constitution. He stated that no American soldier or sailor could be sent overseas to fight a war "except by the constitutional authorities of the

United States."

In addition, Lodge believed that the United States could not fight in every war around the globe and only needed to protect American interests. He said, "Our first ideal is our country…. We would not have our country’s vigor exhausted or her moral force abated, by everlasting meddling and muddling in every quarrel, great and small which affects

the world."

On November 15, the chamber was still considering the treaty when for the first time in its history, the Senate successfully voted to invoke cloture, cutting off debate on the treaty. Four days later, on November 19, the Senate voted on Lodge's resolution for ratification subject to the reservations. The vote was 39 in favor and 55 opposed. As a

two-thirds vote being required, the resolution failed.

The senators who favored ratification of the treaty without reservations had joined with the "irreconcilables," those who opposed the treaty under any circumstances, to defeat the reservations.

The Senate then considered a resolution for ratification of the treaty without reservations. The vote was 38 in favor and 53 opposed. A two-thirds vote being required, the resolution failed.

The final blow occurred on March 19, 1920, when the treaty with reservations was again defeated, 49 in favor to 35 against. Unable to win ratification, in 1921 Congress approved a separate peace treaty, known as the Knox–Porter Resolution, formally ending hostilities with Germany and the Austro-Hungarian government. In signing a separate peace

treaty, the U.S. avoided the requirement to join the League of Nations.

The Lodge Reservations

The Lodge Reservations

While Senator Lodge was open to joining the League of Nations, he was only open to doing so if its Charter was changed to reflect American institutions, integrity and role under the Monroe Doctrine.

On September 16, Lodge introduced his 14 ‘reservations’ to the League of Nations for Senate consideration. Unfortunately space will not allow us to print all of Senator Lodge’s reservations, however, the key ones, which were eventually incorporated into the Charter of the United Nations are:

- The United States so understands and construes Article I that in case of notice of withdrawal from the League of Nations, as provided in said article, the United States shall be the sole judge as to whether all its international obligations and all its obligations under the said Covenant have been fulfilled, and notice of withdrawal by the

United States may be given by a concurrent resolution of the Congress of the United States.

- The United States assumes no obligation to preserve the territorial integrity or political independence of any other country or to interfere in controversies between nations -- whether members of the League or not -- under the provisions of Article 10, or to employ the military or naval forces of the United States under any article of the

treaty for any purpose, unless in any particular case the Congress, which, under the Constitution, has the sole power to declare war or authorize the employment of the military or naval forces of the United States, shall by act or joint resolution so provide.

- No mandate shall be accepted by the United States under Article 22, Part 1, or any other provision of the treaty of peace with Germany, except by action of the Congress of the United States.

- The United States reserves to itself exclusively the right to decide what questions are within its domestic jurisdiction and declares that all domestic and political questions relating wholly or in part to its internal affairs, including immigration, labor, coastwise traffic, the tariff, commerce, the suppression of traffic in women and

children, and in opium and other dangerous drugs, and all other domestic questions, are solely within the jurisdiction of the United States and are not under this treaty to be submitted in any way either to arbitration or to the consideration of the Council or of the Assembly of the League of Nations, or any agency thereof, or to the decision or

recommendation of any other power.

- The United States will not submit to arbitration or to inquiry by the Assembly or by the Council of the League of Nations provided for in said treaty of peace any questions which in the judgment of the United States depend upon or relate to its long-established policy, commonly known as the Monroe Doctrine; said doctrine is to be interpreted

by the United States alone and is hereby declared to be wholly outside the jurisdiction of said League of Nations and entirely unaffected by any provision contained in the said treaty of peace with Germany.

- The Congress of the United States will provide by law for the appointment of the representatives of the United States in the Assembly and the Council of the League of Nations, and may in its discretion provide for the participation of the United States in any commission, committee, tribunal, court, council, or conference, or in the selection

of any members thereof, and for the appointment of members of said commissions, committees, tribunals, courts, councils, or conferences, or any other representatives under the treaty of peace, or in carrying out its provisions; and until such participation and appointment have been so provided for and the powers and duties of such representatives

have been defined by law, no person shall represent the United States under either said League of Nations or the treaty of peace with Germany or be authorized to perform any act for or on behalf of the United States there under; and no citizen of the United States shall be selected or appointed as a member of said commissions, committees,

tribunals, courts, councils, or conferences except with the approval of the Senate of the United States.

- The United States shall not be obligated to contribute to any expenses of the League of Nations, or of the Secretariat, or of any commission, or committee, or conference, or other agency organized under the League of Nations or under the treaty or for the purpose of carrying out the treaty provisions, unless and until an appropriation of

funds available for such expenses shall have been made by the Congress of the United States.

- If the United States shall at any time adopt any plan for the limitation of armaments proposed by the Council of the League of Nations under the provisions of Article 8, it reserves the right to increase such armaments without the consent of the Council whenever the United States is threatened with invasion or engaged in war.

It has been suggested that had the United States become a member of the League of Nations, it would have also provided support to France and Britain, possibly making France feel more secure, and so encouraging France and Britain to oppose more fully the rise of German militarism, thus making the rise to power of Hitler and his Nazi Party less

likely.

Failure of Disarmament & Demise of the League

Article 8 of the League of Nations gave the League the task of reducing "armaments to the lowest point consistent with national safety and the enforcement by common action of international obligations." A significant amount of the League's time and

energy was devoted to this goal, even though many member governments were uncertain that such extensive disarmament could be achieved or was even desirable.

Article 8 of the League of Nations gave the League the task of reducing "armaments to the lowest point consistent with national safety and the enforcement by common action of international obligations." A significant amount of the League's time and

energy was devoted to this goal, even though many member governments were uncertain that such extensive disarmament could be achieved or was even desirable.

The League Covenant assigned the League the task of creating a disarmament plan for each state, but the Council devolved this responsibility to a special commission set up in 1926 to prepare for the 1932–1934 World Disarmament Conference. Members of the League held different views towards the issue. The French were reluctant to reduce their

armaments without a guarantee of military help if they were attacked; Poland and Czechoslovakia felt vulnerable to attack from Germany and wanted the League's response to aggression against its members to be strengthened before they disarmed. Without this guarantee, they would not reduce armaments because they felt the risk of attack from Germany was

too great.

The Disarmament Commission obtained initial agreement from France, Italy, Spain, Japan, and Britain to limit the size of their navies but no final agreement was reached. Ultimately, the Commission failed to halt the military build-up by Germany, Italy, Spain and Japan during the 1930s. The onset of the Second World War demonstrated that the League

had failed in its primary purpose: the prevention of another world war.

The origins of the League as an organization created by the Allied powers as part of the peace settlement to end the First World War led to it being viewed as a "League of Victors." The League's neutrality tended to manifest itself as indecision. It required a unanimous vote of nine, later fifteen, Council members to enact a resolution; hence,

conclusive and effective action was difficult, if not impossible. It was also slow in coming to its decisions, as certain ones required the unanimous consent of the entire Assembly. This problem mainly stemmed from the fact that the primary members of the League of Nations were not willing to accept the possibility of their fate being decided by

other countries, and by enforcing unanimous voting had effectively given themselves veto power.

Another important weakness grew from the contradiction between the idea of collective security that formed the basis of the League and international relations between individual states. The League's collective security system required nations to act, if necessary, against states they considered friendly, and in a way that might endanger their

national interests, to support states for which they had no normal affinity. Moreover, the League's advocacy of disarmament while at the same time advocating collective security meant that the League was depriving itself of the only forceful means by which it could uphold its authority.

The League’s inability to stop Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 emboldened Adolf Hitler, who in 1936 sent troops back into the Rhineland, an area that was supposed to remain a demilitarized zone according to the Treaty of Versailles.

The area known as the Rhineland was a strip of German land that borders France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. This area was deemed a demilitarized zone to increase the security of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands against future German aggression. This move was the first of many direct violations of the Treaty of Versailles by Adolf Hitler.

Again, Great Britain and France did nothing substantial in reaction to this break of the treaty. Due in part to this lack of reaction, Adolf Hitler would soon begin to take over other lands throughout Western Europe, and the world would again experience war.

At the 1943 Tehran Conference, as the tide of battle in WWII was turning against Germany, the Allied powers agreed to create a new body to replace the League: the United Nations. The designers of the structures of the United Nations intended to make it more effective than the League. Many of the reservations to the League, first raised by Senator

Lodge in 1919, were addressed and rectified in the new United Nations charter.

The final meeting of the League of Nations took place in April 1946 in Geneva. Even though the League failed to achieve its ultimate goal of world peace, it did manage to build new roads toward expanding the rule of law across the globe; strengthened the concept of collective security and gave a voice to smaller nations, and most importantly of

all, it laid the groundwork for the creation of the United Nations.