I have elsewhere quoted Genera!

Butler's assertion that in his

interview with the governor and the

mayor of Annapolis, "they said all

Maryland was ready to rush to arms and

that the enthusiasm of the people of

Annapolis could not long be

restrained." The only proof at hand to

contradict this is the letter of Mayor

Magruder, who makes no allusion to it,

but does state what reason they

assigned for objecting to the landing

of the troops. I think it may be

fairly implied that the mayor, in

this, gives substantially the whole

story of the cause which prompted them

to seek the interview with Butler. I

have already shown conclusively that

there was not the slightest danger of

an uprising of the people of Annapolis

against the troops, who were called

"invaders" by Mr. Blank in his frantic

appeals to those same people to rise

and repel them; appeals which aroused

no enthusiasm, but actually met with

derision. I cannot say that Mayor

Magruder did not apprehend some act of

violence on the part of inconsiderate

secession sympathizers towards the

troops, when it was supposed the

Seventh New York Regiment was about to

march through the city, as he went

about summoning a posse to quell any

hostile demonstration; but his

apprehension was that such an act

would take the form of stone throwing

by some thoughtless individuals, not a

concerted attack by a body of

citizens. And the mayor did this on

the afternoon of the same day he and

Governor Hicks had, according to

General Butler, declared that the

enthusiasm of the people of the city

could not long be restrained. I

observed, too, that the mayor was

discreetly summoning known loyal

citizens to act as the posse referred

to. A day or two elapsed, however,

before any considerable number of the

troops marched in a body through the

town. But they did come into the city

from the camp in the Naval Academy,

either singly or in small squads, to

purchase such things as they needed or

desired, and not one of them was

molested.

There seems to have been a tendency

on the part of General Butler to

magnify the dangers he encountered, or

thought he was encountering, in

hastening to the defense of

Washington. He makes much, in his

book, of the wild rumors that met him

in Philadelphia, and on his passage

from that city to Perryville, of the

supposed hostile attitude of the

people of the State. Yet he saw no

signs of such hostility in any portion

of Cecil county, along the line of the

railroad over which his troops were

transported, nor at Perryville, where

he seized the ferryboat Maryland. Was

it a coincidence, or a trick of the

imagination, that credits the governor

of the State with repeating rumors,

the falsity of which had already been

abundantly demonstrated by his own

experience?

|

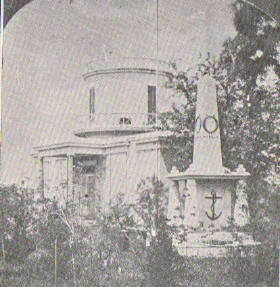

Monument to

Officers and Sailors who perished

in the war with Tripoli |

The truth is that there was not the

slightest danger of all Maryland, or

of any part of it, "rushing to arms."

A few rails were probably taken up

from the track of the Annapolis and

Elkridge Railroad, and the only engine

of the road in Annapolis was partially

disabled; but the road was nowhere

guarded by armed men, as Butler states

the governor informed him it was. Any

damage to the railroad and to its

engine was done by a few irresponsible

and foolish people.

The riot in Baltimore was not as

extensive nor as serious as was

generally reported and believed, and

it is very doubtful whether the

rioters ever contemplated a march to

Annapolis and an attack on the Naval

Academy. But for the burning of the

bridges on the Philadelphia,

Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad,

Butler could have gone to Washington

with his troops by rail without

encountering much opposition. I am

convinced that if, instead of going to

Annapolis, he had diverted his course

to Baltimore and landed at Fort

McHenry, he could have proceeded to

Washington without difficulty. I am

confident he could have quelled the

mob and put an end to the riot in

Baltimore with his single regiment. He

would have found in Baltimore, as he

did in Annapolis, many loyal men to

assist and advise him in his

movements. His seizure of the

Washington Junction of the Baltimore

and Ohio Railroad, at the Relay House,

7 miles from Baltimore, was suggested

to him at Annapolis. Its importance is

a strategic point was well known to

numbers of citizens. I had, myself, in

traveling between Annapolis and

Frederick, which I did frequently,

gained a full knowledge of the

locality; but it was Mr. Purnell, the

comptroller of the treasury, who

suggested that we call Butler's

attention to it. We went together to

Butler's headquarters, at the Naval

Academy, and gave him the information

we possessed concerning the importance

of occupying the Junction with

government troops, against a possible

raid upon it by the Confederates. This

was only a day or two after his

arrival at Annapolis.

It is true, the collision between

the men of the Sixth Massachusetts

Regiment and the mob in Baltimore, on

the 19th of April, 1861, had a

depressing effect upon the unionists

of the State. But that was due mainly

to the misrepresentations with which

reports of the occurrence were

colored. The report carried to

Annapolis and elsewhere was that some

persons in a crowd of men, women and

children, standing on the sidewalk at

Gay and Pratt streets, watching the

troops marching by, were fired upon

and several of them killed, for no

other reason than that somebody in the

crowd jeered at and taunted the

soldiers. No other cause was assigned

for an apparently murderous assault

upon the defenseless people. But it

was added that the alleged outrage had

aroused the whole city to frenzy; that

thousands of citizens tad jailed,

hurried to the scene and attacked the

troops with no other weapons than

paving stones, but with such fury that

their march through the city was

obstructed and that no other troops

would be permitted to pass that way to

Washington.

That was the story as it was told

to me by an exultant secessionist,

who, with a crowd of people of like

mind, was shouting in tones of

triumph, over and over, again and

again: "Hurrah for Maryland! Hurrah

for Maryland! Hurrah for Maryland." I

was at my home when I heard *is outcry

and hurried out to the street to

ascertain its cause. I did not think

of questioning the truth of what was

told me and returned to my home

greatly depressed and sick at heart. I

told my good wife what I had heard and

the fear that it might lead to the

secession of the State. To this she

replied, with womanly intuition,

"Wait; that is not the true story.

Don't worry; wait until we hear the

truth about it. It will all come

right." Her words cheered me, while

they did not entirely relieve my

anxiety. But she was right, and the

truth came the next morning and

confirmed her judgment. The soldiers

were not the aggressors, but were

pursuing their march in a perfectly

orderly manner when they were assailed

by the mob, and only fired upon their

assailants when no other method of

defending themselves was possible.

I have always entertained a

suspicion that the riot in Baltimore

was not as spontaneous as it appeared,

but that it was fomented by men among

the secessionists who were personally

interested in the efforts to make the

State a member of the Southern

Confederacy. Those men saw the last

hope of the success of their plans

vanishing as Federal troops began

pouring down from the North, and it

does not seem imaginary to suspect

that they quietly prompted some of

their followers to begin an uprising

in Baltimore which they hoped would

speedily be spread throughout the

State and end in carrying her out of

the Union in a whirlwind of

enthusiasm. The wild rumors

persistently circulated, that all the

people of the State were ready to rush

to arms to oppose the Federal troops,

probably had their origin in a purpose

to carry such a program into effect.

But, whether the suspicion does or

does not rest upon a reasonable basis,

it is clear that the riot in Baltimore

utterly failed to provoke a response

from the people outside of the city.

They were excited, to be sure, but

nowhere was there anything like a

concerted or formidable movement to

oppose the march of Federal troops

through the State. In fact, that is

putting it too mildly. None of the

troops encountered any opposition

whatever except the Sixth

Massachusetts Regiment, at the hands

of the rioters on Pratt street, as

already related. A Jew members of an

Anne Aruudel county cavalry company

came into Annapolis in uniform about

the time the New York Seventh Regiment

landed at the Naval Academy, and it

was whispered about that they were

seeking to ascertain whether an attack

on the troops was advisable. They

strolled about the streets with their

sabers dangling at their sides, but

made no hostile demonstration and soon

disappeared. I believe they had no

hostile intention, either, as some of

the members of the company were

pronounced unionists and subsequently

enlisted in the Union army and fought

in defense of the country. There were

a few militia companies scattered

about the State, but I have heard of

only one, the membership of which

approximated a unit in favor of

resisting Federal authority. That was

a Carroll county company, the officers

of which were strongly in favor of

secession and offered its services to

aid in resisting the passage of

Federal troops through Baltimore. It

was subsequently disbanded by the

United States military. There was

another company in Carroll county

composed almost, if not quite,

exclusively of unionists. It was

commanded by the late George E.

Wampler, and the late Col. William A.

McKellip was its first lieutenant.

But to return to another feature of

the subject: It seems to me that no

importance can be attached to the

suggestion that the return of the

Democratic party to power in the

State, by an overwhelming majority,

after the war v, as a confession of

the sympathy of the State with

secession. It did not return to power

by the name "Democratic" alone, but

adopted the name of

"Democratic-Conservative" party.

Issues had then entirely changed. It

was no longer a question of union or

disunion. The Union was saved. That

was a fact patent to the dullest

intellect and many loyal citizens felt

themselves free to form new political

alliances and thousands of them united

with the opposition to the Republican

party, the natural successor of the

Union party of the State. Among these

thousands were many of the most

prominent leaders of the unionists

during the war, such men as Governor

Thomas Swann, ex-Governor Augustus W.

Bradford, General John S. Berry,

Reverdy Johnson, William H. Purnell,

Judge William P. Maulsby, General

Edward Shriver, Col. William J.

Leonard, General John W. Horn, Col.

Edwin H. Webster, John V. L. Findlay,

Joshua Biggs, Robert Fowler and many

others of about as much prominence.

These men were, without doubt, in most

instances, actuated by principle and

what they considered just and

sufficient cause. That cause I believe

was principally hostility to unlimited

negro suffrage. That question was

thrust upon the People soon after the

close of the war, as a consequence of

the conflict between President Johnson

and Congress. The universal

enfranchisement of the negroes was

exceedingly distasteful to many of

those who had been active supporters

of the Government during the war, and

when ex-Governor Bradford, who had

been one of the most zealous and

influential unionists in the State,

appeared upon the hustings and

counseled Union men to vote for the

new party, he easily carried

multitudes with him.

I had, personally, an interesting

experience in winning back to the

Republican party a staunch old

unionist in Frederick county, who had

made up his mind to follow the

ex-Governor. He was a man I had known

from my boyhood, a plain, unassuming

farmer. While visiting at my boyhood's

tome soon after Governor Bradford had

spoken at a mass meeting in Frederick,

I was invited lo address a Republican

gathering in the village. After the

meeting my old friend came to me and,

in evident perplexity, informed me

that I had unsettled him in purpose

concerning his proper course as a

voter. He said that Governor Bradford

had convinced him that he ought to

vote the Democratic-Conservative

ticket, and that, until he heard my

address, he had fully made up his mind

to do so, but was then in doubt on the

subject. At the end of a long talk

with me he had determined to stand by

the old party. This he did and

remained to the end of his life an

ardent Republican. But. while its

advocacy of negro suffrage was the

chief cause of the hejira of so many

unionists from the Republican party,

oilier causes had weakened the party

long before the close of the war.

Presdent Lincoln's Emancipation

Proclamation had alienated a number,

especially in the slaveholding

sections of the State; the unfortunate

contest between the State Central

Committee and the Union League, of

which I have already spoken, had a

detrimental effect upon the zeal of

some of those who were on the side

which suffered defeat, the abolition

of slavery by State action, in 1804,

completed the alienation of many who

had grown lukewarm in the cause and

added others to the number; the

practical disfranchisement of many

Southern sympathizers aroused sympathy

for that class of citizens and their

re-investiture with the right of

suffrage was espoused by Governor

Swann, ex-Governor Bradford and many

other strong unionists.

It is but proper to say here,

parenthetically, that the action of

election officers in debarring

secessionists from the exercise of

this right, was confined chiefly to

Baltimore Guy, the counties bordering

on Pennsylvania and some of the

counties on the Eastern Shore. There

was little or no restraint upon voters

in Southern Maryland.

Governor Swann espoused the cause

of the disfranchised citizens with

ardor, and appointed election officers

who did not discriminate against any,

not even those who had borne arms

against the State and General

Government. Of these thousands came

into the State from the South, seeking

to mend their broken fortunes, and

thus augmented the opposition to the

party which had stood loyally for the

Union throughout the war.

Governor Swann was severely

censured by many for his course, not,

perhaps, because it was not just, but

because he was charged with having

done so for a price his election by

the legislature to the United States

Senate. I heard the story of this

alleged bargain told on the floor of

the State Senate during the discussion

of a bill to repeal what was known as

the Eastern Shore law, a statute that

required one of the United States

Senators to be a citizen of that

section of the State. It was told by

Levin L. Waters, then State Senator

from Somerset county. Mr. Waters was

one of the beneficiaries of the

governor's action and spoke in favor

of the repeal of (he law as a

preliminary to Mr. Swann's election to

the Upper House of Congress, as the

repeal was considered necessary to

make such an election valid. Mr.

Waters declared unequivocally and in

the strongest language that he would

vote for the bill because he had

bargained to do so He assorted that an

agreement had been made with the

governor to elect him United States

Senator as the consideration for his

appointment of election officers who

would restore the lost rights of

disfranchised citizens, and that he

felt bound to carry out the bargain.

The Eastern Shore law was repealed,

Governor Swann was elected United

States Senator, and the law was then

promptly reenacted. For some reason

the genet, or refused to accept the

high office to which he had been

chosen and which, it was said, it had

been the ambition of his life to

attain. One cause assigned for this

was a rumor that, in consequence of

the circumstances under which he was

elected, the Senate would reject him.

It was also said that he was

influenced by a suspicion that

Lieutenant Governor C. C. Cox who

would have succeeded him in the

gubernatorial office, was not in

sympathy with the new combination and

might hamper the legislature in its

purpose to call a constitutional

convention, the design of which was to

oust from office all the Union men in

the State. This design was really

carried into effect and the convention

vacated all the offices.

Whatever may be said about this

alleged bargain between the Democrats

and Governor Swann, I believe he would

have made the appointments of election

officers of the character desired if

no such an agreement had been entered

into. He was intensely hostile to

negro suffrage of any sort. Long

before the appointments were to be

made he had requested an interview

with me at the executive chamber and

when I called informed me that he

wished to talk with me about the

suffrage question. He said that if

negroes were universally enfranchised

it would not be more than five years

before Maryland would have a negro

governor and legislature. That the

State would become a veritable Mecca

for all the negroes of the South who

would flock into her by the hundreds

of thousands.

Without expressing an opinion upon

the propriety of universal suffrage

for the blacks I assured him that I

had no fears, in that event, of the

dire consequences he apprehended. He

became very much excited and used some

very harsh language in the discussion

that followed. We parted in anger and

he never spoke to me afterwards, I did

not have an opportunity to tell him,

during the conversation, that I was

not committed to the universal

enfranchisement of the negroes at that

time. 1 did believe in a qualified

negro suffrage, based upon education,

the possession of property, and

military service.

I believe Governor Swann was a

sincere unionist. It was well known at

the beginning of the Civil War that he

was opposed to secession, but there

was some doubt about his attitude upon

maintaining the Union by coercion.

Subsequently, however, he gave the

Government his unqualified support and

in 1864 was in favor of the adoption

of the Constitution by which the

slaves in the State were emancipated.

After his term as governor expired he

was repeatedly elected to the Lower

House of Congress as a Democrat.

I believe that all the causes

leading to the overthrow of the

Republican party in the State, other

than hostility to negro suffrage, were

far less than that in their combined

effect. Many of the more than thirty

thousand voters who remained true to

the party, felt decided repugnance to

their association with negroes,

politically, but maintained their

party fealty because they believed in

Republican principles generally and

were attached to the party because it

had saved the Union from dissolution.

At this day it is known there are many

citizens of the State who are voting

with the Democrats, but outside of the

negro question are Republicans in

principle. Of the leading unionists

whom I have named as having united

with the Democratic-Conservative

party, Ex-Governor Bradford, William

H, Purnell, Edwin H. Webster, and John

V. L. Findlay eventually returned to

the Republican fold.

In this narrative I have not

intentionally omitted any circumstance

which might in the slightest degree

disprove the claim I make that

Governor Hicks arid a majority of the

people of the State were loyal to the

cause of the Union. Yet I would not

undertake to say that she would not

have been forced into secession, as I

believe Virginia was, against the will

of a majority of her citizens, if the

legislature had been called together

at an early period of the secession

movement. Such an act on the part of

the governor would have been construed

as an invitation from hi n to the

Confederate Government to send troops

into the State, and Maryland might, in

that case, have repeated the

experience of her neighboring sister.

When Virginia seceded she was already,

practically, under the control of the

Confederate Government. General

Butler, in his book, page 257, tells

of a circumstance which forcibly

demonstrates the truth of that

assertion. The day after the people of

Virginia had voted on the ordinance of

secession, Major Carey, who

represented Col Mallory, commander of

the secession military force about

Hampton, sought an interview with

Butler by a flag of truce. Butler was

then commanding the Union troops in

that locality and Carey sought the

interview for the purpose of securing

the return, to Col. Mallory, of three

of his negro slaves who had escaped

and made their way into the Federal

lines. Butler declined to return the

negroes and declared them "contraband

of war," a phrase which he undoubtedly

invented, although his claim to have

done so has been disputed. Then Major

Carey inquired whether the passage of

families desiring to go North would be

permitted, and to this General Butler

replied: "With the exception of an

interruption! at Baltimore, which has

now been disposed of, travel of

peaceable citizens through to the

North has not been hindered: AND AS TO

THE INTERNAL LINE THROUGH VIRGINIA,

YOUR FRIENDS HAVE FOR THE PRESENT

ENTIRE CONTROL OF IT."

I have recited this incident as

stated by Butler as conclusive

evidence that Virginia was then

entirely under the control of the

Confederate military, and that

balloting upon tie ordinance of

secession was conducted under that

surveillance. It can never be known

with absolute certainty that a

majority of the people of the State

were in favor of her secession. The

extreme probability is that if those

who were opposed to the ordinance to

carry her out of the Union had voted

against it instead of remaining away

from the polls, as many of then did

under restraint, the ordinance would

not have been adopted. But what a

price Virginia paid for her action,

whether it was voluntary or otherwise.

It is a possibility that Maryland

might have followed her example if a

convention had been called before the

National Government passed into the

control of those who were determined

to prevent the dissolution of the

Union. The unionists, in that case,

would have resisted secession to the

best of their ability, but the State

would almost certainly, have been

occupied by Confederate soldiers and

the loyal people would have had an

uphill fight. That contingency,

happily, did not arise, because of the

sturdy refusal of the governor to call

a special session of the legislature

until it was too late to take

effective steps to bring about the

secession of the State. Members of the

legislature were elected in 1859, when

the question of secession was not

mooted, but as both branches were

strongly Democratic, there was no

doubt about their proclivities. Some

of the Democrats, it is true, were

strong unionists, but probably an

equal number of the American party

members went over to the secessionists

and there is no doubt that a

convention to vote the State out of

the Union would have been convened if

an extra session of the legislature

had been held in time for such action.

And then Maryland would have shared

the sad fate of Virginia.

I maintain, therefore, that it was

the firm resistance of Governor Hicks

to the immense pressure brought to

bear upon him from within and without

the State, to induce him to place her

in a position to co-operate with the

States of the South that kept Maryland

anchored to the Union. And this was in

harmony with the desire of a decided

majority of her people. Her "bent" was

to the Union, not against it. In fact,

there were few secessionists per se in

the State. Her people, with a very few

exceptions, desired the preservation

of the Union. As late as in February,

1861, I circulated a petition in

Annapolis praying Congress to adopt

the Crittenden compromise measure, and

I do not remember that a single

Southern sympathizer refused to sign

it. All wanted the South back in the

Union; but those with Southern

proclivities were determined to join

in the disunion movement, if no method

short of war could have been employed

to prevent it, and hence the clamor

for an extra session of the

legislature.

Thus far I have said nothing about

the more than 60,000 men sent by

Maryland into the Union army and navy.

The records of the adjutant general's

office at Washington place the number

at more than 62,000. But their

participation in the war on the side

of the Government was emphatic

evidence of the loyalty of her people.

It is true, that numbers of

Marylanders entered the Confederate

service to fight against their own

State. But those who did so were

numerically far below those who

entered the Union service. Many of the

prominent unionists whose names I have

mentioned fought for the preservation

of the nation.

And now, to sum up: I think I have

demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt

that Governor Hicks and a majority of

the people of Maryland were loyal to

the Government of the United States

before and daring the Civil War. As

over against the implication of

disloyalty or instability of purpose

on the part of the governor,

predicated upon his Monument Square

speech, his alleged order to burn the

bridges of the P. W. and B. Railroad,

his protest against the landing of

Federal troops at Annapolis, and his

statement that he had changed the

place of meeting of the legislature

because it was not proper for it to

meet in a city under control of United

States soldiers, we have:

1. His statement to me, on his

return from Baltimore the morning

after his speech in Monument Square,

that his utterances on that occasion

were made under duress, his life

having been threatened; his assurance

that he would not desert his loyal

friends and his declaration that "the

Union must be preserved."

2. His emphatic denial that he gave

an order for the burning of the

railroad bridges, or gave his assent

to that act.

3. His frank avowal of loyalty in

the interview, in my presence, with

the man who called himself Col.

Harrison. the day after the attack of

the mob on the Massachusetts troops in

Baltimore.

4. His action in authorizing Mayor

Magrudar and myself to select only

loyal men to whom the State arms were

to be distributed, and his doing that

at. the very time when he was

protesting to General Butler against

landing his troops at the Naval

Academy.

5. His emphatic declaration to

Judge Handy, the commissioner from

Mississippi, that Maryland was not

going with the new Confederacy.

6. His declaration to me that,

notwithstanding his protest against

the landing of Butler's troops, he

wanted them to land, and that the

protest had only been made for the

purpose of deceiving the secessionists

and retaining some hold upon them.

7. His explanation that his real

purpose in selecting Frederick as the

place at which the legislature should

meet was to have it surrounded by a

thoroughly loyal populace.

8. His acknowledgment to me that he

committed a grave error in protesting

against the landing of the troops and

his appeal to my knowledge of his

unfaltering loyalty.

9. And above all other evidences,

his determined stand against convening

the legislature in extra session while

there was an opportunity remaining for

it to take action to carry the State

out of the Union. If there were no

other evidences of his loyalty this

one thing should stand as indubitable

proof of it.

And what stronger proofs of the

patriotic devotion of a majority of

the people of the State to the Union

could be given than their votes, which

elected Union candidates to Congress

in June, 1831, and a Union governor,

by an overwhelming majority, in

November of that year. And it should

not be overlooked, in this connection,

that at the Presidential election in

1864, President Lincoln carried the

State over McClellan and received a

sufficient number of votes to

constitute a majority of the entire

voting population. The results of

these elections are not offset by the

actions of an ephemeral mob in

Baltimore, while their significance,

as indications of the loyalty of the

people, is emphasized and confirmed by

the failure of the secessionists to

poll a third of the votes of those

entitled to the suffrage, at the

special election for members of the

House of Delegates, in Baltimore,

while the mob spirit was still

prevalent in that city at the breaking

out of the war.

I have shown, too, that the wild

rumors of an uprising of the people of

the State against the Government, so

freely circulated immediately after

the attack on the Massachusetts troops

in Baltimore, were utterly without

foundation. That no such uprising was

anywhere threatened. The story of Mr.

Blank's vain appeal to the people of

Annapolis to "rise and repel the

invaders." sufficiently negatives the

assertion that the people of the State

Capital were ready to rush to arms

against the Northern troops. The

undisturbed passage of General Butler

from Philadelphia to Annapolis, with

his troops, was in itself a proof that

the people were nowhere preparing to

dispute the march of the soldiers who

were hurrying forward to the defense

of the National Capital. There is not,

indeed, a scintilla of evidence that

anywhere in the State the people

contemplated armed resistance to the

Government. This only proves, however,

that they were quiescent. Their

active, positive unionism was shown in

the elections to which I have referred

and to the open stand taken by so many

prominent men, some of whose names I

have introduced in this narrative, and

by large masses of the people

generally.

The little incident connected with

the discussion I had with Col. Pugh,

in the summer of 1860, as I have

elsewhere related it; the violence

with which Judge Mason was threatened

by working men in the meeting at the

Assembly Hall in Annapolis, in

February, 1861, when he advocated

secession; the gratification of the

crowd of working men on Taylor's

wharf, on the afternoon of April 21,

1861, when I denounced any outrage on

the flag as meriting the condign

punishment of the perpetrator, were

all incidents marking the drift of

public sentiment as distinctly as a

true weather vane indicates the

direction of the wind.

And so I hold, and believe have

proved, that Maryland's part in saving

the Union, was the voluntary action of

a majority of her people.

It would be difficult to

over-estimate the extent of that part

in the great work, or to gauge the

importance of Maryland's fidelity to

the Government, in its far-reaching

influence and effect upon the struggle

for national unity, She furnished her

full quota of the men who made up the

great armies of the Republic, and by

voluntary State action she wiped the

stain of slavery from her organic law,

releasing a hundred thousand slaves

from bondage. Mr. Lincoln assured me

that he regarded that act as of

immense advantage in the Union cause.

Sometime in the latter part of

September, 1834, after the convention

which framed the Constitution

abolishing slavery had adjourned and

the instrument was pending

ratification or rejection by the votes

of the people, I had an interview

'with him on a personal matter and

when that was disposed of was about to

retire; but he detained me by saying:

'Stop, I want to talk to you. What are

you Marylanders going to do with your

Constitution?"

These, as nearly as I .can recall

them, were his exact wards, and my

reply was: "That is very doubtful,

sir."

With an expression of incredulity

on his face he exclaimed: "You surely

do not mean that." . I saw that he was

startled and disposed to question my

own attitude toward the abolition of

slavery in the State and to doubt my

sincerity in replying as I had done to

his inquiry, but was constrained to

answer in the affirmative and to

inform him that I was perfectly

serious in advancing that opinion.

Then he said, in a tone that implied

doubt about the value of my judgment:

"Well, sir, you are the first man from

Maryland who has intimated such an

opinion to me. All my information

derived from many of your leading

citizens, gives me the assurance that

the Constitution will be adopted by an

overwhelming majority."

The conversation had become very

embarrassing to me, but I felt sure of

my ground and believed that it was

important that Mr. Lincoln should be

undeceived in his anticipation of an

easy victory. I therefore challenged

the judgment of those upon whose

information he was relying. I said to

him, without reservation, that they

ware either in ignorance of the true

state o£ affairs or were not frank,

enough, to tell him what they really

thought about it. I gave him a brief

analysis of the situation; showed him

that every secessionist in the State

would vote against the Constitution;

that with very few exceptions, every

unionist slaveholder would do likewise

and would also exert an influence upon

his non-slaveholding friends against

emancipation without compensation, as

many of them believed that slaves were

legitimate property, of which the

owners should not be deprived without

receiving some remuneration. I

concluded this summary by the

prediction that nothing could save the

Constitution from defeat, except the

votes of soldiers in the camps and

field, as the convention which framed

the instrument had provided a plan by

which the soldiers from the State were

given an opportunity to vote on the

question.

As I proceeded to explain the

reasons which impelled me to believe

there was grave doubt about the result

of the election, Mr. Lincoln became

more and more agitated and when I

ceased, exclaimed: "You alarm me sir!

you alarm me! you alarm me! I did not

dream there was the slightest danger

of such a calamity as the defeat of

this Constitution. I fear you and

others of our friends in Maryland are

not alive to the importance of this

matter and its influence upon the

conflict in which we are engaged. The

adoption of your Constitution

abolishing slavery will be equal to a

victory by one of our armies in the

field. It will be a notification to

the South that, no matter what the

result of the war shall be, Maryland

is lost to that section forever."

We were seated during this

conversation and Mr. Lincoln did not

seem in haste to end the interview,

but I finally rose and then, standing

beside me with his hand on my shoulder

and his tall form towering above me,

he exclaimed: "I implore you, sir, to

go to ,work and endeavor to induce

others to go to work for your

Constitution, with all your energy.

Try to impress other unionists with

its importance as a war measure, and

don't let it fail! Don't let it fail."

I assured him that I would not only

vote for the instrument, but that I

was doing all that I could in its

favor. I called his attention to his

own powerful influence and exhorted

him to exert it to the utmost, as it

would require the best efforts of the

friends of emancipation to secure the

adoption of the Constitution. This

ended the interview. The result of the

election proved the accuracy of my

judgment concerning it. About 2500

soldiers voted in the camps and in the

field, but the majority for the

Constitution was less than 400.

I have told the story of this

interview with Mr. Lincoln in detail

to exhibit, in its full force, his

opinion of the great service rendered

the Union cause in this one single

act. His exclamation of alarm when I

explained fully my reason for

believing the result of the vote on

the Constitution in doubt, and his

declaration that the adoption of the

measure would be equal to a victory of

one of our armies in the field, are

given in his exact words, and I have

followed very closely his language

throughout the interview.

But after all, what was putting

62,000 men into the army and the

abolition of slavery in the State,

compared with the effect, in other

respects, of the State's adherence to

the Union. That was worth half a

million of men. To unreflecting

readers that opinion may seem to be

wild and extravagant perhaps

ridiculous. But consider, for a

moment, what her secession at any

time before President Lincoln's call

for volunteers would have meant. Look

at the map of the United States and

see that, in that event, the National

Capital would have been surrounded on

every side by hostile territory. That

the shortest distance from Washington

to the border of a loyal State, in a

direct line, would have been more than

fifty miles. That this hostile

territory would at once, upon the

secession of the State, or probably

upon the first official act in the

direction of secession, have been

occupied by Confederate troops and

that, in all human probability, the

National Capital would have been

seized and declared the seal of

government of the new Confederacy.

This is not a vague surmise. The

Confederacy was prepared for war. I

need not repeat at any length the

story of the depletion of arsenals in

the North, by Buchanan's Secretary of

War, to supply the South with

munitions of war. That is a matter of

un-contradicted history. And thus

strongly entrenched and ready for the

conflict, with augmented armies, the

South would not only have been in a

position to long repel invasion, but

would have been prepared for an

aggressive movement against the North,

with a much brighter prospect of

victory than awaited Lee at

Gettysburg.

But that is not all. It is scarcely

problematical, as I have stated, that,

with the secession of Maryland, the

National Capital would have fallen to

the Confederacy, and that would have

meant, beyond a doubt, the recognition

of the independence of the new

Government by every Power of any

consequence in the civilized world.

And following that recognition,

offensive and defensive alliances

would have been formed by the South

that would have made it well nigh

impossible to conquer her. I believe

this theory not only tenable, but

sound and logical, and considering

this view of the subject, the part

played by Maryland in saving the

Union, far transcends that of any

other State.

Astronomical

Observatory and Monument to the

Naval Heroes in Naval Academy |

And for this the country is

indebted to the loyalty of Governor

Hicks, and the men who were closely

allied with him, in resisting the

efforts of the secessionists to bring

the State into line with her seceding

Southern sisters, as well as to the

devotion of. a majority of her people

to the cause of the Union. This fact

cannot be too strongly emphasized, but

it is a fact which the country at

large has seemingly failed to

recognize, because, perhaps, no

historian has deemed it of sufficient

importance even to allude to ii, while

most if not all of them have belittled

the State's part in resisting the

secession movement, by unjustly

attributing it to the military

domination of the Government, when, in

fact, that did not have an existence

till Annapolis was first occupied by

Northern troops, more than a month and

a half after the inauguration of

President Lincoln.

I trust the time will come when the

injustice of this view will be,

recognized and understood by the

people of the whole country and when

the great share of the State in

preserving the nation from dissolution

and disintegration will be generally

recognized and acknowledged.

It is a source of pride and

pleasure to me in my old age to

remember that circumstances placed me

in a position to have some share in

holding Maryland to her fealty to the

Union and to sincerely believe that

her loyalty had much to do with

preventing its dissolution and in

bringing about the causes which have

made the country great and honored

among the nations of the earth, as

well as in preserving "government of

the people, by the people, and for the

people," from a disastrous overthrow.

The reader of this should

understand, also, that this course was

not unmarked by sacrifices on the part

of mast Maryland unionists, sacrifices

of the closest ties of friendship,

and, in many cases, of the tenderest

cords of near relationship. In

innumerable instances brother was

arrayed against brother and friend

against friend. I had, myself, the

experience of alienation from some of

those who were near to me in "kinship

and very close and dear in

association, and from others with whom

I had always been identified in

social, political and other interests.

That was the common experience of

almost all Maryland unionists, than

whom there were none more faithful and

true to the country in the struggle

which reunited the States and made

this one of the greatest, freest and

happiest nations and people in the

history of the world.

As this narrative is designed to

exhibit only the civilian side of

Maryland's part in saving the Union,

no attempt is made to show the part

her soldiery played in the

accomplishment of that most desirable

result. The troops she sent into the

field were not a whit less courageous

than the bravest in arms of their

comrades from other States. They were

Americans first, and after that

Marylanders. The armies of both sides

were largely composed of native born

citizens and when American meets

American, "then comes the tug of war."

It was this quality of persistence and

unfaltering courage in the people of

the North and South alike, that

prolonged the war until the weaker

side was exhausted and the country was

saved.

Special thanks to

John Miller for his efforts in scanning the book's contents and converting it into the web page you are now viewing.